While my favorite trail feature is a ridge line with dramatic valleys to either side, open ledges or exposed slab come in a close second. My beloved Welch-Dickey loop crosses two summits with spectacular views, but what makes it special to me is that so much of the hike is over bare granite slabs- where I can geek out over the exposed geology of the mountain.

Neither mountain is particularly tall- Welch tops out at 2,605 feet and Dickey at 2,734 feet, and the 4.4 miles loop trail is perfect for a few hour outing. Bare summits are unusual for small mountains, but the guide book1 notes that a combination of fire and heavy rains in the early 1800s stripped the summits down to rock.

Time flows slowly on mountain tops— even though some 200 years have passed since the fire, the vast expanses of bare stone remain.

It gives me joy to look out from the summit and pick out the other peaks I’ve stood atop this summer: Tecumseh, Osceola, the Hancocks, and Carrigain.

The trail down from the Dickey summit will follow the ridge line at the top of the exposed slabs, which plunge down into the steepest part of the valley.

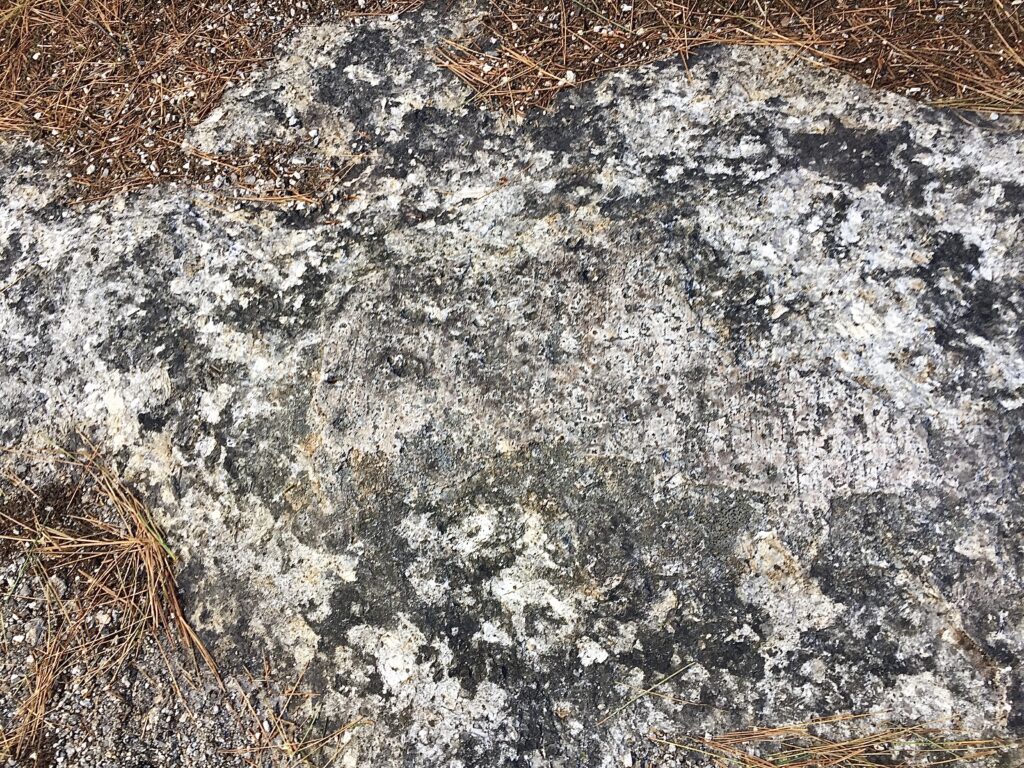

Apart from the views, one thing I love about the bare slab is that I can see the natural history of the mountain laid out in front of me. From the veins of intruding basalt that formed when the granite was still cooling deep underground

To the fractures that split huge blocks along grain boundaries

And the patches of glacial polish where the last ice age rode up an over. I know it’s really hard to see in this photo, but where most of the exposed rock is rough and weathered, this one has a smoothly polished texture, and you can just make out make out faint scratches running vertically along the direction the glacier traveled. Glacial polish is common in the Sierra Nevada, and I saw it in many places in Yosemite National Park last summer, but it’s much more rare in New England, and I’m a little proud to have spotted it here.

Most of the granite on the slabs has a weathered, pock-marked texture which makes it possible to walk up even at an angle. I wonder how much of this weathering happened in the 200-odd years since the peaks were stripped of soil by fire and rain.

I’m always fascinated by the deep pot holes worn into apparently solid rock. Did this begin when the rock was covered with soil and trees, or did wind and water and sun and freeze/thaw cycles start eroding a weakness only once it was exposed to the surface? A hardy fringe of blueberry bushes takes root wherever the smallest amount of soil accumulates in a crack.

Gradually, islands of soil held in place by lichen and plants will spread across the slabs, but if this small island took 200 years to form, I feel quite certain that for as many years as I can walk the earth, I’ll be able to visit the bare slabs on Welch and Dickey.

1 Ken MacGray New Hampshire’s 52 with a View a Hiker’s Guide 2019